Home › State of the States › Annual Features › Cost Containment and Quality Improvement Strategies ›

Cost Containment and Quality Improvement Prioritized by States

The rising cost of health care and new research about variation in quality of care have spurred many states to focus on increasing value in their respective health care systems. States want better value for their health care dollar, first in the public sector and then throughout the health care system. Increasingly, states are considering coverage reform in tandem with improved mechanisms for providing and paying for health care. While much remains to be learned about promoting quality health care at a fair price, some states are leading the way with pilot projects and innovative programs that will inform future federal and state reforms.

Why Is Reform Needed?

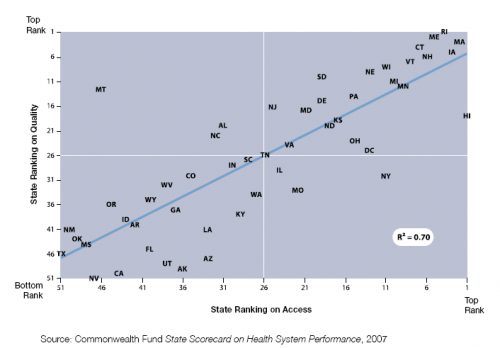

In 2007, The Commonwealth Fund released its State Scorecard on Health System Performance, which revealed wide state-to-state variation in access to care, cost, efficiency, and quality. As shown in Figure 8, quality was highly correlated with access to care, indicating that increased coverage is an important strategy for improving the overall health of a state’s population.

The Scorecard also showed that higher spending levels do not necessarily lead to quality improvement, as confirmed by research from the Center for Health Policy Research, which developed the Dartmouth Atlas. In fact, a recent study of several common conditions demonstrated that higher spending correlates with higher morbidity, lower satisfaction with hospital care, worse communication between physicians, and less access to primary care.[i]

State Ranking on Access and Quality Dimensions

The negative correlation between cost and quality is of special concern in today’s environment of dramatically increasing health care costs. Between 1999 and 2008, the cost of health insurance premiums more than doubled (increasing by 119 percent) while wages grew by only 34 percent.[ii] At the same time, deductibles and cost sharing for those with coverage have been on the rise. Despite paying more than twice as much for health coverage, Americans are buying less comprehensive protection. In addition, with rising costs and increasing enrollment, Medicaid now consumes an average 21.2 percent of state budgets, which is twice the amount of eight years ago.[iii]

Even if cost was not a concern, a large body of evidence shows that the U.S. health care system fails to deliver consistently high-quality care. Care is often poorly coordinated[iv] and falls short of best-practice standards.[v] The seminal 1999 Institute of Medicine report, To Err is Human, shone a light on the pervasiveness of medical errors in the U.S. health care system, estimating 98,000 deaths per year attributable to medical errors.[vi]

Care Coordination and Medical Homes

Many states are exploring the possibility of supporting and strengthening primary care as a way to improve quality and reduce costs. States believe that a strong primary care system can help coordinate patient care, promote prevention and healthy lifestyles, educate patients on their health conditions, and reduce costly emergency room visits and duplication of services.

Investing in relatively inexpensive primary and preventive care as an alternative to costly specialty services and acute care is such an obvious solution that some now worry that primary care providers will soon be asked to solve the full range of problems plaguing the health care system, piling unrealistic expectations on an already overworked and—some would argue—underpaid segment of the medical profession. It is possible that the term “medical home” (and related concepts such as patient-centered primary care and chronic condition management) is quickly coming to mean all things to all people. The challenge for states is to define what is expected from primary care providers; to decide how to pay for additional services such as care coordination, patient education, and health information technology that are not currently part of the fee-for-service payment model; and to determine the target populations for such services.

The following examples describe projects undertaken by states to coordinate care:

- Community Care of North Carolina has a long and successful track record with what it calls Primary Care Case Management (PCCM). Beginning in 1998 with Medicaid providers, Community Care divided primary care providers into regional networks that support quality improvement through the development of standards, data collection and reporting, and the provision of community-based resources such as care managers and patient educators. Both the provider and the network receive a monthly payment per member for each Medicaid patient for care coordination and case management.

Community Care achieved $240 million in savings in state fiscal year 2005–2006. While this figure represents just a fraction[vii] of the total North Carolina Medicaid budget, Community Care realized the savings along with significant quality improvements for Medicaid recipients.[viii] The program is succeeding for several reasons. First, as a provider-led effort, Community Care can easily promote buy-in from a critical group of health care system participants. Second, the regional networks report quality information back to providers so they know when they are not meeting best-practice standards of care. Third, the regional networks provide care coordination and case management services either in a provider’s office or in a community setting, shared by several providers. The North Carolina Community Care program is now trying to spread the model beyond Medicaid providers to all primary care providers in the state.[ix] At the same time, the state is working to develop a demonstration project to apply the model to Medicare patients.

- In 2007, Vermont passed legislation that promotes medical home pilots in communities around the state under the Blueprint for Health. As reported in the 2008 State of the States, the program brings together all payers except Medicare. It establishes community care teams to help with care coordination, patient and provider education, and other patient services. In addition, Vermont has levied a 0.02 percent surcharge on all insurance premiums in the state to create a health information technology infrastructure. The Blueprint for Health launched its pilot communities in 2008.[x]

- Rhode Island’s Chronic Care Sustainability Initiative requires primary care providers to: 1) implement components of an advanced medical home; 2) participate in a local chronic care collaborative; 3) submit data that will be publicly reported; and 4) engage and educate patients[xi]

The program estimates that it represents 67 percent of the state’s insured residents. The state is using the Health Insurance Commissioner’s regulatory power to require insurance plans to: 1) provide a supplemental payment to primary care providers; 2) pay for nurse care managers; and 3) share data and report on common measures.[xii]

The National Academy for State Health Policy conducted a scan of state Medicaid programs and SCHIPs and found that 31 states are working to advance medical home projects.[xiii] Some other states are working to establish medical homes throughout their health care system regardless of payer. States with multi-stakeholder initiatives include Colorado, Louisiana, Maine, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont.[xiv]

Wellness Initiatives

About a quarter of the rising cost of health care can be linked to the growing prevalence of “modifiable population risk factors,” such as obesity.[xv] Patient lifestyles and health choices are one of the primary reasons for the nation’s growing disease burden and related increase in health care costs. Doctors, employers, insurers, and government agencies are looking for ways to encourage Americans to make healthier choices—to prevent disease or to manage chronic conditions once they develop. Despite sharp disagreements about the appropriate solutions for expanding health care coverage and reforming health care financing, there is widespread agreement—both among health care experts and the general public[xvi]—on the value of promoting wellness and prevention.

Many states have started implementing wellness programs as part of their state employee health benefit plans. According to a recent National Conference of State Legislatures survey, 14 states have adopted some type of wellness program for their state employees.[xvii] Examples include the following:

- Alabama recently announced that, as of January 2011, obese state employees will be required either to start getting fit or pay an additional $25 per month toward their premiums. Employees who smoke already pay an additional $24 per month.

- Arkansas state employees can earn up to three days of vacation leave per year by participating in the Healthy Lifestyle program.

- Missouri operates an incentive program for employees, permitting them to save up to $25 per month if they take a personal health assessment and participate in a health improvement program.

- Delaware, Montana, and West Virginia have launched programs that offer screenings, health coaching, fitness, and education to help employees improve their health.

- King County, Washington, operates a comprehensive health and wellness program that saved the county an estimated $40 million between 2007 and 2009.[xviii]

During 2008, both New Hampshire and Florida passed legislation requiring insurance brokers that conduct business in the state to work with health plans in the state to develop a lower-cost insurance product focusing on prevention, primary care, and healthy lifestyle promotion. Both states followed the example set by Rhode Island, which passed similar legislation in 2007.[xix]

Patient Safety

When the Institute of Medicine’s To Err is Human estimated that more than 98,000 deaths per year are attributable to preventable medical errors, it became clear that “business as usual” was no longer sufficient to protect patients; the time for systemic reforms had arrived. The report emphasized that, while all humans make mistakes, systems must be put in place to protect against errors and promote best-practice care. To encourage system improvements, particularly in hospitals, states have undertaken the following:

- Hospitals are required to report serious adverse events, medical errors, or near misses. Some states require these events to be made public while others keep the information confidential but encourage the affected hospital to develop plans to prevent similar errors in the future.

- Collaborative groups have been established to share best practices and promote safe and effective care. To that end, a number of states have established Patient Safety Centers.

- A few states have joined Medicare and national health plans in refusing to pay for “never events” in their Medicaid and state employees health plans. “Never events” are errors such as wrong-site surgeries or hospital-acquired infections that hospitals should be able to prevent.[xx]

Price and Quality Transparency

Recognition is growing that it is time to engage health care consumers in the effort to promote affordable, high-quality health care. An increasing number of health plans have high deductibles and copayments designed to steer patients to high-value providers and services. However, in many cases, consumers lack appropriate information for making informed choices. For that reason, both federal and state policymakers have made data collection and price and quality transparency a priority.

A recent issue brief by the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices outlines four strategies used by states to promote data collection and transparency.[xxi]

- Setting a Common Vision—State governments have been able to set and articulate priorities that require data sharing and transparency. Examples of the policy goals that transparency can help achieve include improving chronic disease care, reducing medical errors, enabling patients to “comparison shop,” and promoting quality improvements among providers.

- Convening Key Stakeholders—States command the influence to bring stakeholders to the table. Ongoing conversations can lead to agreements on data-sharing standards, common claims processes, and payment incentives to providers who deliver high-value care.

- Regulating Providers and Insurers—States can use their influence as regulators to require insurers and providers to share data. Such information can then be made public and used as a tool for patients or shared only with providers and purchasers. When providers see how they compare with similar providers, they often take steps toward quality improvement. The hurdle for states is that they do not have the authority to compel self-insured employers or Medicare to share information.

- Leveraging State Purchasing Power—States can require data sharing, compliance with data standards, and price and cost transparency through contracts in the Medicaid, SCHIP, and state employee health benefit plans.

The type of data collected by states must reflect their plans for data use. Several states are leading the way in developing all-payer claims databases. Such databases are typically used for billing purposes so they are most useful for assessing costs, but they may also be used for making some quality and value determinations. States engaged in chronic care collaboratives or other practice improvement programs have developed patient registries to collect additional information about patient outcomes, such as blood pressure readings and blood sugar levels. States seeking to use data for health information exchanges will need additional data such as laboratory values, physician notes, and test results, although such data (e.g., chart reviews and laboratory results) are much more expensive and difficult to obtain. Much of that information is still housed in file cabinets and not generally available by electronic means.

Health Information Technology and Exchange

There is broad agreement that electronic health information technology and communications can improve quality and save costs in the health care system. Not surprisingly, 70 percent of states responding to a 2007 survey reported that “eHealth”[xxii] was a very significant priority while no states reported that it was not a priority. When asked about their top state eHealth priorities, 25 of 42 responding states listed adoption of a health information exchange (HIE). In addition, 12 states reported HIE policy development as a priority, 9 states listed development of electronic health records, and 7 states listed e-prescribing.[xxiii] The Commonwealth Fund’s Commission on a High Performance Health System estimates that the investment of 1 percent of health insurance premiums in health information technology could save the country $88 billion over 10 years out of projected national health expenditures totaling $4.4 trillion.[xxiv]

Preventable Hospital Readmissions

Both state and federal policymakers are increasing their focus on preventable patient readmissions after hospital discharge. A 2007 MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Council) report found that 17.6 percent of Medicare patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge and that the Medicare program spent $15 billion on readmissions in 2005.[xxv] The prevention of readmissions requires an effective transition from inpatient providers to outpatient providers and effective medication management. In many cases, the current payment system does not offer financial incentives for coordination of post-discharge care. Policymakers recognize that efforts to prevent readmissions can have significant return on investment, saving the system money while fostering patient health.

Conclusion

President Obama’s health care plan includes many initiatives aimed at containing costs and improving quality. Several of the initiatives align with recent state efforts, including the support of chronic care management programs, investment in health information technology, coordinated and integrated care, required transparency in cost and quality information, and promotion of patient safety.[xxvi] The challenge facing the new administration will lie in coordinating with and building on state efforts in these areas. The significant variation in health care delivery models both between and within states will make it critical for federal policymakers to take advantage of the on-the-ground expertise of state governments.

[i] Fisher, E.S. et al. “The Implications of Regional Variations in Medicare Spending, Part 2: Health Outcomes and Satisfaction with Care,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 138, No. 4, pp. 288-98.

[ii] According to data collected in the Kaiser/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits. See http://ehbs.kff.org/images/abstract/EHBS_08_Release_Adds.pdf.

[iii] Fiscal Year 2007 State Expenditure Report, National Association of State Budget Officers, Fall 2008. http://www.nasbo.org/Publications/PDFs/FY07%20State%20Expenditure%20Report.pdf.

[iv] “Framework for a High Performance Health System for the United States,” The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System, New York: The Commonwealth Fund, August 2006.

[v] McGlynn, E.A. et al. “The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 348, No. 26, pp. 2635-45.

[vi] Kohn, L.T. et al., eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1999.

[vii] The total Medicaid budget in North Carolina for state fiscal year 2007–2008 exceeded $11 billion.

[viii] Willson, C. “Community Care of North Carolina,” February 2008. http://statecoverage.org/node/226.

[ix] Community Care of North Carolina Web site, http://www.communitycarenc.com/.

[x] Vermont Blueprint for Health, http://healthvermont.gov/blueprint.aspx

[xi] Koller, C. “The Rhode Island Chronic Care Sustainability Initiative (CSI-RI): Translating the Medical Home Principles into a Payment Pilot,” power point slides at the 2008 conference of The National Academy for State Health Policy Web site, available at www.nashp.org/Files/Koller_Precon_NASHP2008.pdf.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] “Results of the State Medical Home Scan,”The National Academy for State Health Policy, October 2008. www.nashp.org/_docdisp_page.cfm?LID=980882B8-1085-4B10-B72C136F53C90DFB.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Thorpe, K.E. “The Rise in Health Care Spending and What to Do about It,” Health Affairs,Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 1436-45.

[xvi] Connolly, C. “Obama Policymakers Turn to Campaign Tools,” Washington Post, December 4. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/12/03/AR2008120303829.html?hpid=topnews

[xvii] “State Employee Health Benefits,” National Conference of State Legislatures Web site, http://www.ncsl.org/programs/health/stateemploy.htm.

[xviii] Dow, B. “King County’s Health Initiative,” power point slides at AcademyHealth Summer Meeting, July 2008, available at http://www.statecoverage.org/node/240

[xix] State of the States 2008: Rising to the Challenge, State Coverage Initiatives, AcademyHealth, January 2008.

[xx] For more information on “never events,” see www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/press/release.asp?Counter=1863.

[xxi] Quality and Price Transparency as an Element of State Health Reform, National Governor’s Association Center for Best Practices, August 2008. http://www.nga.org/portal/site/nga/menuitem.9123e83a1f6786440ddcbeeb501010a0/?vgnextoid=a6a0fbc0578bb110VgnVCM1000001a01010aRCRD.

[xxii] The survey defined “eHealth” as any health care practice supported by electronic processes and communication, including health information technology (HIT) and health information exchange (HIE).

[xxiii] Smith, V. et al. “State Health Activities in 2007: Findings from a State Survey,” February 2008. www.healthmanagement.com/files/1104_Smith_state_e-hlt_activities_2007_findings_st.pdf.

[xxiv] Schoen, C. et al. “Bending the Curve: Options for Achieving Savings and Improving Value in U.S. Health Spending,” The Commonwealth Fund, December 18, 2007. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/publications_show.htm?doc_id=620087.

[xxv] “Promoting Greater Efficiency in Medicare,” MedPAC Report to Congress, June 2007.

[xxvi] Information about Obama’s health care plan taken from www.barackobama.com/pdf/issues/HealthCareFullPlan.pdf.

See This Year's Analysis

Read this year's analysis in the following articles:

- State and National Health Care Reform: A Case for Federalism

- Lessons Learned from State Reform Efforts